Building a culture of connection and collaboration in the new world of work

INTRODUCTION

Work has changed. Organisations are increasingly distributed and disconnected. Engagement levels are low and workplace loneliness is high. Traditional hierarchies are being questioned, and implicit biases called out. And expectations among employees are higher, particularly among Generation Z, their demands more vociferous and publicly visible.

Creating cultures that both support and develop individuals is ever tougher as HR leader continue to wrestle with hybrid working practices and budget-squeezes, amidst a myriad of other challenges. But the value of embedding a true learning culture - where people feel empowered to connect and collaborate on their own terms, and can lock in what they learn in the flow of work - is indisputable.

It’s what drove organisations like Google to champion peer-to-peer learning programmes, and mutual support and the exchange of experience and skills is increasingly becoming the bedrock of development programmes. That’s because, from a psychological point of view, connecting and collaborating with a peer - someone who understands, and crucially shares, your context - unlocks empathy and combats feelings of insecurity, uncertainty or isolation.

While mentoring and coaching provide directional or one-way support; peer interactions are inherently inclusive and mutual

Peer support has long been recognised as a cornerstone of clinical therapy because it provides a safe space where people are not only accepted but truly understood.

And peer support drives trust. People’s experiences are treated as being equally valid and important, and it allows for both sides of a partnership to give and receive, with neither side feeling indebted to the other. It is an inclusive, accessible and flexible process.

When applying these principles at work, the same is true. Individuals can support, advise and even challenge each other with neither needing to be the expert, and both feeling like they have contributed and benefited on equal terms. While mentoring and coaching provide directional or one-way support; peer interactions are inherently inclusive and mutual. They break down barriers, levelling the career support playing field.

Ultimately peer conversations can create transformative thinking partnerships for the long term; relationships that far outlive traditional mentoring or coaching approaches. But embedding a peer-led development culture can be tough without fully understanding the key psychological drivers that underpin the need to do so.

To help make that a little bit easier, we’ve considered the theory and practical steps involved in harnessing the power of peers. We’re sure you’ll have ideas of your own too and we’d love to hear them; that’s the magic of collaboration!

1. ACCOUNTABILITY

Making peer pressure a positive force

As children we are told not to give in to peer pressure. That it's bad. But inherently humans are swayed by the opinions of those around us; we are intrinsically social animals and we want to be accepted, to be part of the herd. And as we learn, we gather critical information from the people around us and the environment we find ourselves within. We constantly mirror, mimic and build on the inputs we receive in order to keep learning what it means to be us.

This can result in negative outcomes when we let those inputs lead us towards decisions and behaviours that are bad, or even dangerous. But when we use the influence of others to keep us on track, or to push us to achieve difficult things, we can actually harness that very same pressure to positive effect.

This is where peer pressure becomes something far more palatable: shared accountability.

If accountability can be defined as taking personal responsibility for one’s own actions, then shared accountability can be seen as working together with someone else to hold each other responsible and to inspire success.

If accountability can be defined as taking personal responsibility for one’s own actions, then shared accountability can be seen as working together with someone else to hold each other responsible and to inspire success.

Building on the same theory that’s seen millions of people lose weight, stay sober or make gains in the gym; championing accountability partnerships within work and career settings can result in people making real progress towards their goals - whether organisational or personal. According to Vance, Lowry and Eggett’s 2015 Accountability Theory, we take more responsibility for our own actions when we perceive the need to justify them to someone else.

In ‘The Chimp Paradox’ (2012), sports psychologist Dr Steve Peters explores how having someone ‘on your side’, spurring you on and calling you out if you don’t make the progress you want can help control negative impulses and have profound positive effects on both performance and wellbeing. Much like the old adage that a ‘problem shared is a problem halved’, finding the right person to collaborate with can make holding yourself accountable much easier.

And accountability matters. In empowered organisational cultures, those that promote autonomy and ownership of actions, accountability is the next step towards ensuring productivity and performance. It’s not much use having the autonomy to determine your own course of action if you don’t follow through, or if that autonomy actually leads to a lack of responsibility and even to blame shifting. So necessarily, autonomy and accountability go hand in hand.

Accountability partnerships can transform intentions into reality. James Clear, author of ‘Atomic Habits’ (2020), recognised the gap between intention setting and taking action. The awareness that your actions are being monitored serves to psychologically bridge this gap and can be the difference between inaction and action (Vance, Lowry and Eggett 2015). That’s because as humans we’re wired to seek approval, and to judge our own growth and development by how we’re viewed through the eyes of others.

Shared accountability also leads to increased fortitude resulting from the practice of giving and receiving feedback and support. This reinforcement of positive thinking, through connection and collaboration with others, helps foster resilience.

As poet John Donne famously wrote, no one is an island, and we all need input, support and reinforcement from others in order to be our best - and most productive - selves.

Enabling positive peer pressure

Praise the process not the person

Feedback is personal but we should take care to make sure that the delivery of it is as non-judgemental as possible. This can be hard because we often take the behaviours of others to signify ‘who they are’ rather than ‘what they have done’. This ‘Fundamental Attribution Error’ (Ross, 1977) can mean that the feedback we give oftens stings and can demotivate rather than encourage positive change.

Feedback that works is clear, honest, direct and humble. It creates distance between the behaviours you have observed and the person, allowing them to explore the impact of their actions (or inaction) in a more objective way. Offering honest feedback, without a side serving of blame or judgement, is the difference between forced progress and shared accountability.

Focus on outcomes not outputs

Goal setting has been intrinsically linked with motivation since Edwin Locke first observed the positive impact it had on task performance in the 1960s. Goal setting consistently delivers positive change to the lives of individuals because it provides focus and direction. But change can be hard and the goals we set ourselves can begin to feel unachievable if progress isn’t made quickly enough or we feel we’re failing.

We are not machines, and often our intended goal may change and shift depending on the process we take to get there or the context we find ourselves in. True accountability partners know this and offer encouragement of any positive outcome that moves us closer to our goal; they focus on the bigger picture and how we want to feel, rather than analysing outputs that may never add up to real change.

Use accountability to drive productivity

In order to be productive, we need to stay on track despite all of the curveballs our role might throw at us. Feeling accountable to someone else creates an ‘expectation of evaluation’ (Lerner and Tetlock, 1999) and is a powerful motivator.

It’s the principle that fitness apps like Strava are built on, with the wider community keeping individuals accountable to their goals and motivating them to be more productive by awarding each other kudos. The same can be replicated in real life, in the workplace, with accountability partners helping to inspire and motivate each other to do whatever they want or need to achieve.

Case Study: How Google harnessed Peer Power

Google has always believed in the importance of learning, and that the best kind of learning happens in the flow of work. That was the driving philosophy behind the creation of our g2g (googler-to-googler) peer learning programme, launched way back in 2007. It’s since become a bedrock of Google’s learning culture, with over 80% of employee development delivered through peer interactions.

When conceiving this approach, we quickly realised that, by harnessing the skill sets and knowledge already residing in our employees, we could create meaningful social learning opportunities that our people actually wanted to engage in. And by switching our focus from more directive forms of instruction to collaborative knowledge exchanges, we were better able to embed the 70:20:10 principle within the organisation, designing more accessible programmes that catered for different learning styles.

Key to the success of g2g was leadership buy-in and employee empowerment. At first we thought it was important for managers to ‘approve’ participation, but we quickly found that a permission-based approach limited ownership and engagement amongst participants, and instead leaders encouraging, rather than allowing, participation - and crucially supporting Googlers to make time for it, created both momentum and value.

Ultimately a clear and sustained focus on putting the right support structures in place to promote social learning is what underpins truly effective learning cultures, and the enduring success of g2g - 15 years and counting - is testament to this.

2. AUTONOMY AND EMPOWERMENT

Encouraging intrinsic motivation

Empowered organisations trust their employees. CEO of Starbucks, Howard Shultz, says that we all, ‘want to be given responsibility to help solve the problem and the authority to act on it’. When we feel that the work we do matters and that we have the agency to manage our own careers, we are more likely to feel competent; a feeling that keeps us engaged in both the work we do and the organisation we work for.

A sense of competence is one of the most important psychological drivers for motivation (Deci and Ryan, 1985) but it can only truly be achieved when we take full accountability for our actions. Praise is nice, but is no replacement for the deep sense of pride we feel when our accomplishments are self-driven.

In his 2009 book ‘Drive’, Dan Pink identifies three elements that need to be present in working life to encourage what Deci and Ryan (1985, 2000) call ‘intrinsic motivation’: autonomy, mastery and purpose.

If accountability can be defined as taking personal responsibility for one’s own actions, then shared accountability can be seen as working together with someone else to hold each other responsible and to inspire success.

He found that we will put huge amounts of discretionary effort into our work if we believe in what we are doing, have the opportunity to use our unique skills and have the autonomy to make our own decisions.

Successful careers are no longer characterised by a linear promotion structure that aims to get you ‘to the top’. In fact, people in senior positions often report high levels of anxiety and imposter syndrome. This lack of self-belief is rooted in a lack of empowerment. If we don’t actively engage with our development and progress as we move through our careers, we become disassociated with our achievements.

We can’t own our success because we haven’t psychologically processed it. It’s like following instructions on a sat nav; we find our way, but we don’t connect with the journey itself (and we almost certainly won’t remember the route we took). We can’t take any personal credit for finding the way to our desired destination, eroding our ability to feel accomplished and contributing to a lack of motivation and engagement.

In ‘Multipliers’ (2012) Liz Wiseman states that organisations should create an environment where employees have ‘permission to think’, as an act of trust that allows intrinsic motivation to flourish. When we have the space and time to process our development - and we know that 70% of this happens ‘in the flow of work’ - we create a conscious connection between our intentions and our actions.

↓MORE ↓

We are able to replicate what we learn and pass this on to others. We feel connected to our achievements and feel encouraged to achieve more.

The role of an organisation is not merely to provide development opportunities, but to allow people to take charge of their learning experiences and build reflective practice into their working lives. In order to create this culture, everyone needs to have clarity about the role they play in their organisation and what is expected of them.

Leaders play a crucial role in this process, making their role increasingly geared towards expectation setting and support as opposed to task setting and monitoring performance. Rather like an orchestral conductor, the leader keeps everyone on track while each person maintains their own sense of mastery and is responsible for the quality of their contribution.

In a post-pandemic world, people increasingly value flexibility over status. What this really means, is having a sense of autonomy (HBR, 2021). People want to feel that their employer trusts them to fulfil the demands of their role, to the best of their abilities, without the constraints of enforced working hours, office environments or even traditional organisational structures.

Opportunities for development should be provided as a ‘place to think’ (Wiseman) rather than a place to passively receive information. Given the opportunity, people will invest their time wisely in doing what is right for them (Pink, 2009). They will choose development if they feel empowered to do so and if they can see the immediate benefit to their career, but are more

Building an autonomous and empowered culture

Create clarity

Make sure that everyone knows not just what they need to do but why their contribution is so important to the success of the organisation.

Be honest

When things change (which they inevitably will) make sure that everyone gets the memo. Give people the right to reply, even if decisions are final and unwavering. Knowing our views will be heard is about as empowering as it gets.

Boost collaboration

Involve people in decision making processes and encourage cross-departmental working to break down silos between teams.

Give great leadership

Leaders should be skilled in the art of communication, not just delegation. Empowerment thrives when leaders feel comfortable enough in their own position to let go of a desire to control and encourage their team to thrive instead. Leaders need their own support and autonomy to be in a position to enable their teams in this way.

Encourage reflective practice

Creating opportunities for your employees to share experiences and learn from each other’s successes and mistakes will build confidence and connection with both their work and their colleagues. It is the most effective way to inspire continuous and adaptive learning.

Where traditional mentoring falters

Mentoring has a great reputation. It’s considered the gold standard for development and diversity programmes alike because it allows more junior people to benefit from the experience, knowledge, support and often advocacy of a more senior employee. While there is no doubt that it has its place, there are some fundamental issues. One of which is the motivation of people seeking mentors which, in some cases, is more about exposure than development.

This ‘glory mentoring’ is really just a way to network with influential people. There is nothing inherently wrong with that but, while only 1.5% of senior roles are held by black employees in the UK and just 32% by women, and as people often mentor in their own image (blame their cognitive and social biases, not them), there is a high chance that this process is doing anything but levelling the playing field in the diversity stakes.

There is also an assumption in traditional mentoring that those more senior know best. But, with a workforce who are less driven by hierarchy than ever before and vast differences in expectations from four hugely different generations, this traditional mentoring structure feels like it’s getting out of step with what people actually want and need in order to develop.

Finally, there’s the issue of scale. There are simply not enough senior leaders to go round and, those who are willing to mentor their keen young proteges, are often over-stretched and, as a result many traditional mentoring programmes don’t stand the test of time

3. CONNECTION AND COLLABORATION

Combating loneliness and isolation at work

Loneliness at work manifests itself in a variety of ways and can be hard to spot as, on the surface, employees can appear to be engaged and well-socialised within the workplace. However, it comes down to an intrinsic, subjective belief held by individuals that they are only superficially connected to others, and that they have few people they can turn to for support.

This sense of loneliness can strike at any time, from nervous isolation at the start of a career or a move to somewhere new, to those in leadership roles who feel they have no one to turn to for help anymore. And loneliness can have profound impacts on both physical and mental health, raising levels of cortisol - the stress hormone - substantially, and potentially even leading to increased risk of early mortality.

While this might sound alarmist, it’s not that surprising when you consider the vital role love and belonging (i.e. friendship and connection) plays within Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs; with only food, water and safety being more important. Having a trusted support system and strong connections with others is key to maintaining mental well-being, lowering levels of anxiety and depression, as well as preserving physical health by strengthening immune systems.

That’s because human brains are hardwired to seek connection with others and to share our knowledge with them.

According to neuroscientist Matthew Lieberman “when we are first taking in new information, part of what we do is consider whom we can share information with and how we can share it in a compelling way.” (M. Lieberman, Social: Why Our Brains Are Wired to Connect, 2013)

In fact, forming connections around knowledge sharing is crucial to building our self-esteem and self-worth; we are programmed to seek and share information with others in order to be recognised and accepted by them. In turn this combats loneliness and isolation, and influences what we remember and how we learn.

If accountability can be defined as taking personal responsibility for one’s own actions, then shared accountability can be seen as working together with someone else to hold each other responsible and to inspire success.

↓MORE ↓

Combating loneliness and isolation at work [continued]

Connection and friendship at work also influences performance. According to Gallup, we want to feel that the work we do is worthwhile, and having trusted supporters and confidants helps enhance that feeling, making us feel more engaged, and thus increasing our effort levels. So organisations that help foster meaningful relationships can expect higher levels of loyalty and performance as a result. (Gallup, 2012)

Building secure connections also helps to drive collaboration, when we seek to overcome problems and obstacles by working together with others. Having a trusted set of supporters to turn to, and workshop challenges with, can lead to breakthroughs and innovations that are hard to accomplish alone.

And collaborative cultures - where people feel truly empowered to share their ideas and opinions, and are subsequently recognised for them - help combat siloed thinking as well as loneliness and isolation. By engaging and connecting with others to solve problems, we learn from each other, sharing our expertise and surfacing new perspectives.

Collaboration, however, is about more than sharing knowledge for mutual benefit, and it also goes beyond the coordination and exchange of resources, or even cooperation to achieve a shared goal.

True collaboration comes when people are clear that they care as much about the success of their partner(s) as they do about their own success, and vice versa. The collaborators will happily share both the risks and rewards. Not only does this build a culture of trust, it also increases morale as we feel invested in the success of others.

We’re wired to connect: to work with people we trust, who understand and respect our points of view, to share objectives with others, and to seek and exchange knowledge.

Ultimately, as Lieberman outlines, we’re wired to connect: to work with people we trust, who understand and respect our points of view, to share objectives with others, and to seek and exchange knowledge. Collaboration makes this possible.

Three principles of a connected, collaborative culture

Trust

We cannot expect trust, we have to encourage and nurture it. We must create an environment where collaboration is commonplace; where, in order to succeed, you are expected to share ideas and gain insight and input from others. An environment where this behaviour is valued as highly as our individual efforts.

If we’re given both the permission (Tamm, 2015) and the opportunity to consistently prove our credibility and reliability (Maister, 2000), as well as the confidence that our colleagues and thinking partners have our best interests at heart; we can drop our defences and start to trust each other.

Openness

In order to truly connect, we need to understand each other. We can’t expect to build trusting relationships if we are unwilling to hear the point of view of others or share our own, honest, opinions. Communication that is guarded feeds our defensive nature (Tamm, 2015) and erodes trust.

Collaboration is a democratic process and this means that we need to feel heard and understood when we share our views, even if these views challenge the opinions of others. And, we need to be allowed to show vulnerability and not feel diminished by this.

Respect

Respect grows in environments where our input is thoughtfully considered and valued. And where respect feels like a mutual exchange based on merit, not hierarchy. We can earn respect through our contributions, and come to respect others based on the positive exchanges we have with them. We bring a lot of ourselves to work and we expect - whether we realise it or not - the people we work with and the organisation we work within to show us the courtesy of recognising our efforts.

Organisations with a healthy culture, understand the importance of modelling mutual respect; actively creating opportunities for us to share constructive feedback with each other and celebrate successes together. Giving everyone credit when and where it is due. Respect helps to cultivate a culture of inclusion and equality in which collaboration can thrive.

Why connection drives employee engagement

"The theory of self-determinism is at the very heart of employee engagement, driving motivation and psychological growth. But self-determinism can’t be achieved without connection - it’s a need innate within all of us.

By experiencing a sense of relatedness, or connection to others, we build our intrinsic motivation, which in turn helps create a culture of psychological safety, accountability and performance.

That’s why, at Peakon, we focused on measuring some of the more intangible, abstract factors that contribute towards that sense of connection and belonging, and ultimately how motivated and engaged someone feels about work"

4. CONTINUOUS, SOCIAL LEARNING

Harnessing our human desire to fit in

Human beings learn from each other. From the day we are born we absorb social cues and form social connections in order to make sense of the world. The information we gather helps us to develop our character and we continue to learn through both our actions and interactions throughout our lives. We are incredibly suggestable and adaptable with a limitless potential to, as Albert Bandura (1977) proposed in his theory of social learning, ‘observe, model and imitate the attitudes, behaviours and emotional reactions of others’.

Learning is not a linear process where information becomes ‘locked in’. It is fluid, complex, continuous and inevitable. We learn every day, whether we like it or not, and it is in ‘informal’ learning environments that we learn the most. McCall, Lombardo and Eichinger’s 70/20/10 model was created in recognition of this and has been the cornerstone of any good learning and development strategy since its conception in the 1980s.

The reasoning behind social learning theory is simple: we all want to fit in. Exactly where and with whom we want to fit in varies between people, but the search for understanding, meaning and belonging is the driving force behind all human behaviour - even for the most neurodiverse amongst us.

Learning organisations understand this fundamental and unavoidable human need. They know that the very best way to share information, create a healthy culture and develop the capabilities and motivation of their teams, is to weave learning opportunities into the everyday fabric of the organisation.

Buddy systems, mentoring and continuous feedback are all ways to build learning opportunities into the 70% of our working lives; reserving more formal learning like workshops, development conversations and coaching as opportunities to introduce new concepts and support focused individual development.

There is more nuance to social learning theory than simply observation of / interaction with others equalling behaviour change. Just because we have learnt something, does not mean that we will act on this knowledge to change our own behaviour. Mental state, cognitive and personal bias and motivation will all determine whether or not true learning actually takes place.

Simply put, we can choose what we learn, even if we are not always consciously aware that a choice is being made. Learning organisations cannot control this process, but they can influence it by creating the right environment and

Embedding social learning

Create time and space

Perceived lack of time is the single biggest barrier to learning, so genuinely and purposefully creating space for peers to connect can help people to appreciate the utility of these interactions and make time for them. Social learning is not reliant on in-person interactions but it does require us to lift our heads up from our individual work and allow for regular conversations and collaboration with others.

Learn together

Encouraging more structured and varied connections that complement existing work relationships can build greater autonomy, trust and provide a safe space for peers to share their concerns, ideas and experiences. As Nancy Kline puts it, we all need ‘time to think’ and we come up with our best ideas when we have the opportunity for these to be heard by the people who just ‘get it’.

Foster a feedback culture

We cannot learn without feedback but when it’s delivered ‘top-down’, feedback can be demotivating and leave people feeling disempowered - even when it’s positive. However, creating a holistic feedback culture is the foundation that effective social learning can be built on. Both hearing feedback from a peer, and feeling empowered to deliver feedback to the people who really have an impact on your work, is often far more useful than receiving feedback from a manager.

Welcome failure

In the spirit of psychological safety, it is important to allow people to learn through their mistakes. We cannot learn unless we are allowed to experiment with new behaviours, skills and ideas. And teams that are allowed to fail are braver, more dynamic and more creative. Having the added accountability to peers, rather than only managers, allows the transfer of learning to take place in a supportive and low pressure environment.

Encourage reflection

Self-reflection is a crucial part of any learning process and reflecting together is critical to the social learning process. When we only reflect on ourselves, we lose sight of the bigger picture. We may not even be aware of the impact our work or behaviour has had on others. We may be overly critical or falsely positive - either way, no change can occur if we don’t allow ourselves to listen to the thoughts and point of view of others.

The problem with coaching

Coaching is a great way to get tailored and personal development with a trusted professional. But, it’s pricey. As a consequence, it’s usually reserved for the most senior leaders or for those on high potential programmes.

It’s difficult to know how effective coaching is. Certainly there is a significant benefit for the individuals who go through this process but, it’s harder to know how this will positively impact the environment that person works within. Coaching should always be just a small part of the development picture for an organisation. Development should be accessible and coaching, by virtue of the cost and time involved, is not.

Coaching is an unregulated profession so both the cost and quality varies wildly. Many organisations have trusted suppliers (often ex employees who have retrained) or internally trained leaders, who provide the service. The challenge for organisations is to make sure that they set a clear standard for their coaches and share their expectations for the process..

To make coaching more accessible, organisations should consider developing the coaching skills of their employees. Simple skills, used regularly can build confidence, encourage autonomy and have a hugely positive impact on the overall culture of an organization.

5. WELLBEING AND PSYCHOLOGICAL SAFETY

Creating a safe and inclusive space to learn

In 2005, the People Operations team at Google conducted a piece of research to find out what makes an effective team. They identified five key dynamics, but ‘far and away the most important’ (Julia Rozovsky, Google) was ‘psychological safety’; taking risks without feeling insecure or embarrassed.

The term, first coined by Harvard’s Amy Edmundson in 1999, describes interpersonal risk; do we feel safe enough with our peers to ask the ‘dumb’ questions or share our point of view, even when it challenges the current order.

Psychological safety is the prerequisite for wellbeing at work to exist

Feeling safe is, according to Maslow’s seminal ‘Hierarchy of Needs’ (1943) a basic human need and the foundation for all human progress. An absence of trust within a team or organisational structure can be a fatal blow to the team’s success and the psychological well-being of the team members (Lencioni, 2002). Without psychological safety, we can feel demotivated, disengaged and, at worst, stressed and anxious.

Psychological safety is the prerequisite needed for well-being at work to exist. There is little point in any organisation investing in a well-being agenda if the average employee doesn’t feel empowered to offer their opinion in a meeting or is scared to make mistakes in their work for fear of reprisal. 89% of people in a recent survey conducted by McKinsey stated that feeling psychologically safe at work is essential to them.

It is the interpersonal nature of psychological safety that is so crucial for organisations to tune in to. Leaders can help to set the right tone by cultivating compassion in their teams (McKinsey, 2020), which can be achieved by encouraging candour and creating opportunities for teams to share their vulnerabilities as well as their ideas.

Peer conversations like these will always occur naturally as we make connections and alliances with people that we have an affinity with, but these can be exclusive and create tension with those who are not invited or able to participate. Actively creating opportunities for peer relationships to flourish for everyone can break down barriers and enable empathy to thrive in open and honest communication.

↓MORE ↓

In this way, psychological safety is a crucial part of the puzzle when it comes to creating a more inclusive environment. When we feel safe we are empowered to ‘speak up’ (Edmondson, 1999) and be heard. There are still questions about whether or not, even the most well-meaning organisations, create safe spaces for all opinions to be considered with equal importance. This creates a disparity between those who feel protected by their working environment and those who do not. There is an opportunity for active, encouraged and structured peer support to fill this gap; making inclusivity central to the process of developing and learning from each other.

Connections and friendships are no longer as inevitably and organically formed when working outside of an office environment. This can leave people feeling lonely, unsupported and can lead to a lack of engagement.

Hudson Jordan, a Managing Director at Charles Schwab, advocates that, ‘creating an environment of involvement, respect, and connection — where the richness of ideas, backgrounds, and perspectives are harnessed to create business value’ is the cornerstone of an inclusive culture.

Having someone, other than your manager, to support you is both life and career enhancing; according to a Gallup survey in 2018, those who have a work ‘best friend’ are seven times more likely to be engaged in their jobs than those who don’t, and connections with peers fuel more productivity and a greater enjoyment of work (Gallup, 2018).

As we navigate hybrid working environments, it becomes even more important to create a psychologically safe culture (HBR, 2021), but doing so is harder than it was pre-pandemic. Connections and friendships are no longer as inevitably and organically formed when working outside of an office environment. This can leave people feeling lonely, unsupported and can lead to a lack of engagement.

Organisations need to do more to put peer-support at the centre of their culture. In doing so, they will protect the well-being of their employees, creating a safe space for everyone to share ideas and vulnerabilities, support each other, learn and grow.

Creating a psychologically safe environment

Welcome vulnerability

Leaders can model this by sharing their challenges, and even failures, helping people to feel safe to do the same.

Create connections

Help people to build relationships with peers across physical, social and cultural boundaries.

Encourage people to speak up

Notice the people who aren’t being heard and give them a platform to share their opinions more often. Specifically, give them a seat at the table (both figuratively and literally) when topics that concern them are being discussed.

Build a ‘yes, and…’ culture

When people share ideas, offer suggestions that further those ideas rather than picking them apart. Even if an idea isn’t right, building on it to encourage creative thinking will not only generate better ideas but will show that all ideas are welcome.

Focus on strengths

When people work with their strengths they are more energised and engaged in their work. Making use of everyone’s strengths for the collective good of a team can boost morale, energy and focus.

Use coaching skills

Asking questions and actively listening is a simple and effective way to make people feel valued and understood. Brush up on your coaching skills and encourage this practice across your organization.

Take a holistic approach

Make sure that people feel well cared for. Many people may need extra support or guidance to do their jobs to the best of their ability. More important than knowledge, do they have the resources, time, support and confidence to be at their best at work?

Overcoming the forgetting curve

According to German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus, when you learn something new you are likely to forget it pretty rapidly unless you put it into practice straight away. That’s because our ability to recall information drops quickly and degrades rapidly over time. Even if that training course you just went on was brilliant, your ability to remember the ‘lightbulb moment’ is slim when you step out of the context within which it was delivered.

In order to process new information, we need a psychological anchor. If the information was delivered in a particularly memorable way, we might find it more easy to recall. But, if like many structured learning interventions, it was just one part of a large body of information, this new piece of learning needs to be reinforced before it can be properly remembered.

Learning needs reinforcement because our brains prefer to follow the well trodden paths of thought they always have. You need to actively re-engage with what you have learnt as soon as you can so that you can process it effectively.

Reinforcement needs to reoccur through the repetition of an action, or working through, in more detail, what you have learnt, why it’s important and how you can use it to best effect. Ebbinghaus calls this ‘spaced learning’.

Because it is easier to remember the things you learn in context, going through this process with someone else and learning together - sharing actions, successes and failures - is a great way to put spaced learning into practice and create the right environment for the information recall that makes learning possible.

IT'S TIME TO HARNESS PEER POWER!

Adopting a peer-led approach to learning is, in a sense, pushing on an open door. We are naturally attuned to seek the opinions of others, especially those with whom we share a mutual respect.

Left to chance, peer relationships may naturally grow but not necessarily provide

the encouragement, strength and optimism needed to effectively support personal or professional growth.

While there are many ways to support people to be their best at work, creating space and structure to allow everyone to build the right peer-support squad for them may be the most simple and effective. It also encourages shared accountability and provides a psychologically safe environment for everyone.

By empowering individuals to connect and collaborate with others, we can build true social learning cultures, and give everyone the permission and inspiration they need to harness the power of peers for themselves.

ABOUT VOCO

Voco is a peer-powered career development platform, combining data-led matching and behavioural psychology to create powerful thinking partnerships. We empower employees to take control of their careers; creating connected, inclusive learning cultures for everyone.

Effortless matching

Voco’s algorithm uses over 150 quantitative and qualitative data points to magically match members. No more guesswork; we help take uncertainty out of matching, making sure people connect with others who can really understand and support them, and vice versa.

Simple and scalable

By focusing on creating valuable thinking partnerships and sounding boards between peers, Voco overcomes the scale limitations of traditional mentoring schemes where mentees almost always outnumber mentors, meaning there really is someone for everyone.

Coaching mindsets

Voco democratises access to coaching-style conversations, using prompts and conversation guides to embed coaching mindsets. By developing skills like active listening, reflecting and reframing; members unlock work-based problems while building valuable coaching skill sets.

Relationships that last

Voco’s carefully curated learning tracks build momentum, while sparking ideas and keeping conversations flowing over multiple interactions. Dynamic feedback loops lock in shared learnings; underlining accountability and building meaningful relationships for the long term.

Inclusive and equitable

Voco offers the space and structure to create opportunities for peer-learning to flourish in a supportive, natural and inclusive way. What’s more, peer partnerships are more equitable than traditional mentoring relationships as both sides contribute and benefit on equal terms, removing implicit hierarchies and power imbalances.

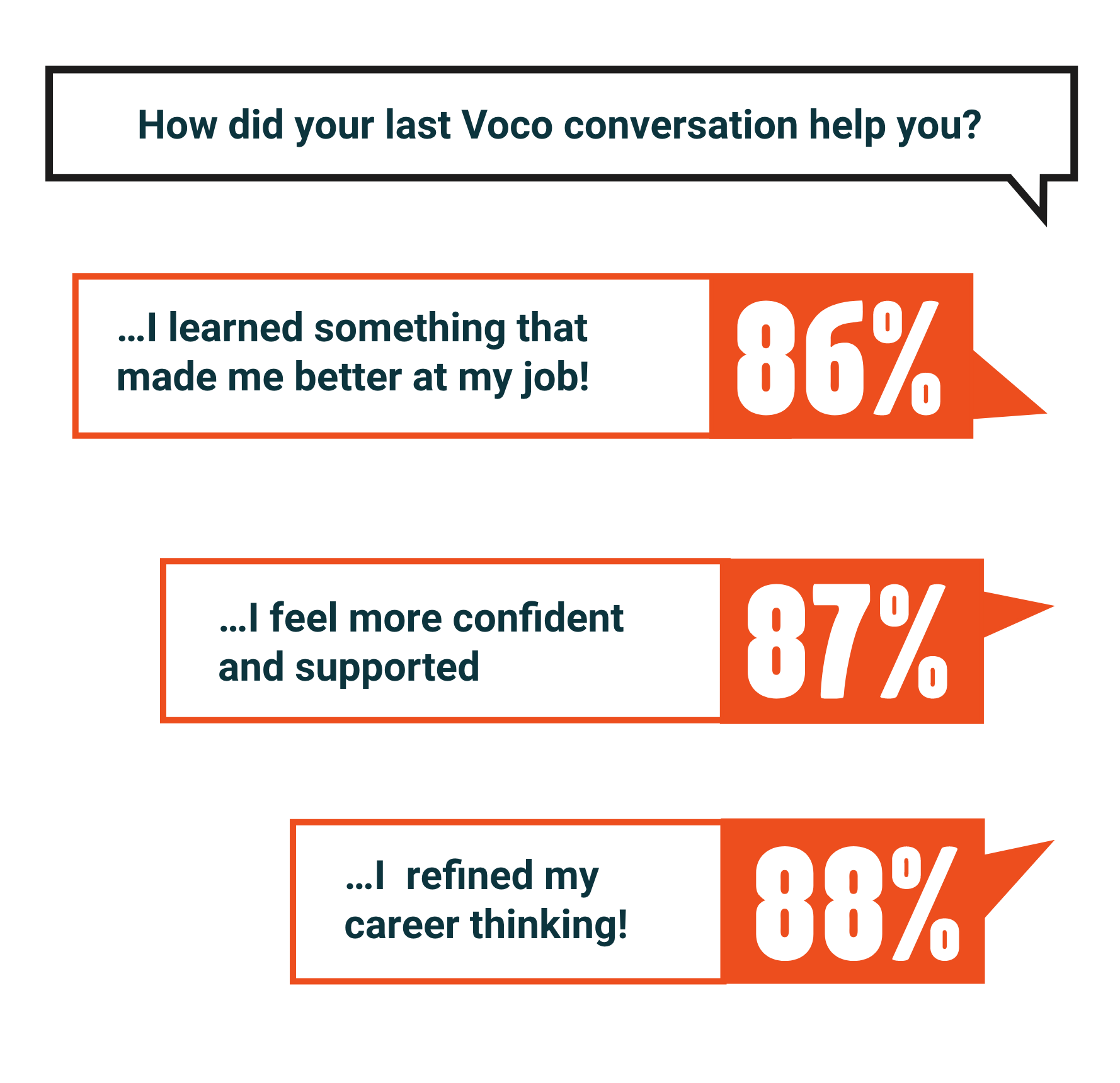

Measurable progress

We empower members to understand and track their career progress and sentiment, and how it changes with each Voco conversation. And we help leaders join the dots between the more intangible benefits of connection and collaboration that result in happier, more engaged people.

Loved by users from

“Voco has taken the Mentoring Collective to a new level, brokering impactful, lasting partnerships that have brought our people closer across the globe. By focusing on who people are in the context of their careers, as well as what they do in their jobs, Voco has helped our people get more tailored support, fresh perspectives and valuable new connections across our organisation.”

-- Elle Gaffney, Head of Talent Development, M&C Saatchi Group

www.joinvoco.com